FCI/SV Standard

Standard No. 166 for the German Shepherd Dog

Origin: Germany

FCI Classification:

Group 1: Sheepherding - Sheep Guardian

Section 1: Sheepherding-dog tested/examined for working qualifications.

Use: Sheepdog with a high degree of versatility and usability; police dog, guide dog, and rescue dog.

A brief history

After the official formation of the German Shepherd Dog Club (SV), with it's headquarters in Augsburg, the next step was to have the breed standard accepted by the German Kennel Club (VDH). Whilst simultaneously the standard had to be agreed upon by all involved with the breed at the time. The SV was effectively launched into life at the first members meeting, held on the 20th of September 1899, where proposals and recommendations of the breed standard were presented by a Mr. A. Meyer and Dr. Stefanitz. Consequently, several gatherings of the members followed with the agenda always to better coordinate the breeding standard; the 6th members meeting on the 28th of July 1901, the 23rd members meeting in Cologne on the 17th of September 1909 - the combined meetings between the then club president and the breed committees were held at Wiesbaden on the 5th of September 1930 and the 25th of March 1961, where, by now, it was apparent that the formation of the (WUSV) (World Union for German Shepherd Dog Clubs) was becoming a reality.

This framework was continuously streamlined, and on the 30th of August 1976 further key decisions for the breed and programme were taken. Proposals and meetings were always catalogued and conclusions monitored until the WUSV Congress on the 23rd and 24th of March 1991 - through the presidents authority, full power was granted to the WUSV.

General appearance

The German Shepherd is a medium size, slightly stretched, strong, dry and well muscled, with strong bones, whilst the whole body must appear compact.

Important size proportions

At the point of the wither, the measurement must be between 60-65 cms in males and 55-60 cms in females. The body length must surpass the wither height by between 10-17%.

Character

The German Shepherd must be self assured, balanced with strong nerves and absolutely impartial behaviour, whilst maintaining a good nature - until pushed to the limit. The dog must be vibrant and easygoing. Furthermore the dog must be courageous, have a strong fighting instinct and possess firm nerves. These are essential requirements since the dog is to be used as companion, guardian, protector and a working sheepdog.

Head

It has to be wedge shaped and it should be proportionate in size to the rest of the body (the length of the head should be approximately 40% that of the wither height), without appearing clumsy, shapeless or coarse or over-long. The general appearance must be dry (no flabby, loose skin). The forehead (whether seen from the front or the side), should not appear to be domed and have only little or no centre furrow.

The ratio between the forehead and the end of the muzzle must be almost 50/50. The forehead width must be the same as it's length. The skull (seen from the top), from the ears to the tip of the nose must consist of smooth lines, whilst having a defined separation between the skull and the muzzle (stop).

The nose

Must be black.

The mouth

Must be strong, well-developed, healthy and complete (42 teeth in total). The German shepherd must have a scissor-like bite, in other words the bottom teeth locking with the top teeth in a scissor-like formation. Furthermore, the upper jaw must overlap the bottom jaw. The definition on the side of the jaw, is positioned in such-a-way, so as the top and bottom layers of the front teeth (top and bottom) must not shut level (directly on top of the other) - the top must over-lap the bottom in a scissor-like close. The bones of the jaws must be well developed so as the teeth are not prematurely worn.

The eyes

Have middle size, almond-shaped and slightly angled, whilst they must not protrude. The eye colour should be as dark as possible. Light eyes are not desirable as they spoil the expression of the dog.

Ears

The German shepherd has ears which are middle sized, firm textured, broad at the base, set high on the skull, are carried erect (almost parallel and not pulled inwards), taper to a point and open towards the front. Tipped ears are faulty. Hanging ears are a very serious fault. During movement the ears may be folded back.The ears should be set high on the skull and carried almost parallel.

Neck

The neck must be strong, well muscled and without excessive, loose skin at the throat. It should be at a 45° angle to the body.

Body

A smooth top line beginning from the back of the neck and continuing in a straight line over a well developed wither and sloping slightly toward the croup - without any visible disturbance. The back is tight, strong and well muscled. The loin is broad, well developed and well muscled. The croup must be long and slightly angled (about 23° to the horizontal), without any disturbance to the topline - it must continue toward the beginning of the tail.

The chest

Must be moderately broad and the brisket should be long and pronounced. The depth of the chest should not be more than 45-48% of the wither height.

Ribs

Must show a moderate curve. It is faulty for the ribs to be either barrel shaped (too round) or slab sided (too flat).

The tail

Is bushy haired on the underside, should reach at least to the hock joint. The ideal length - being to the middle of the hock bones. When at rest the tail should hang in a slight curve like a sabre. When moving it is raised and the curve is increased. Surgical corrections are not permitted.

Forelimbs

The forelimbs - when seen from all sides must be absolutely straight. Viewed from the front, they must be parallel. The shoulder blade and the upper arm must have the same length, be well muscled and be tightly knit to the body. The angle of the shoulder blade to the upperarm - ideally should be at 90° but usually it is acceptable around 110°. The elbows must be close to the body - both in stance and in movement.

The pastern must be 1/3 of the length of the foreleg and an angle of about 20° - 22° to foreleg. Furthermore the pastern should be neither too straight nor too angled (say 20-22°), so as not to deter the dogs stamina.

The feet

Should be rounded, toes well closed and arched. Pads should be well cushioned and durable but not brittle surfaced. Nails short, strong and dark in colour.

Hindquarter

The position of the hindquarter bones are rounded toward the back. When viewed from the back, they are parallel to each other. The upper and lower thigh bones are almost of the same length and create an angle of approximately 120°. The tight must be strong and well muscled. The hock joint must be strong and tight, whilst on a vertical line to the rear feet.

Gait

The German Shepherd Dog is a trotting dog. To achieve this, the limbs must be in such balance to one another so that the hind quarter may be thrusted well forward to the mid-point of the body and have an equally long reach with the forefoot and without any noticeable change in the back line.

The correct proportion of height to corresponding length of limbs will produce a ground-covering stride giving the impression of effortless movement. The head thrust forward and tail slightly raised - balanced and even trotting is seen with a flowing line, running from the tips of the ears over the neck, back and the tip of the tail.

The skin

Tight, without any wrinkles.

Coat

The consistency of the hair: The correct hair type for the German shepherd consists of the undercoat and an overcoat. The overcoat must be made up of dense, straight - hard and close-lying hairs. The hair on the head, ears, paws and legs must be longer and even denser. The hair at the back of the hind legs form a moderate "trouser".

Colour

Base colour should be black with markings of brown, red-brown, blonde and light grey. Alternatively a grey base-colour with "clouds" of black markings and a black "saddle" and "mask". Inconspicuous white markings on the chest, and "brighter" shades on the under- and inner sides of the dog are permitted but not desirable. The nostrils must in all cases be black.

Non-existence of a "mask", bright - until piercing eye colour as well as light/white nails and are coloured tail top are considered as a lack of pigmentation, the undercoat is a slight gray fond. White is not permitted.

Height/Weight

|

Sex

|

Wither height

|

Weight

|

|

Male

|

60 cm to 65cm

|

30 kg to 40 kg

|

|

Female

|

55 cm to 60 cm

|

22 kg to 32 kg

|

Testicles

Male animals must two, apparently normal testicles fully developed into the scrotum.

Faults

Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree.

Serious faults

Departure from the breed standard which has been stated in this context and which affects the usefulness and appearance of the dog, is considered a serious fault. Lacking of pigmentation, heavy and loose dogs, missing or faulty dentition and/or jaw formation.

Faults of the ears

Ears set too low off the side of the skull, soft and tipping at the tops.

Exclusion faults

| a. | A weak character and nervous or nervous biters. |

| b. | Proven (documented) serious "HD" condition. |

| c. | Monorchids, cryptorchids or deformed testicles. |

| d. | Deformed tails and ears. |

| e. | Dogs with deformities. |

| f. | Dogs with missing teeth. |

| g. | Faulty jaws (under- or over shot mouths). |

| h. | Oversize/undersize by more than 1 cm from the set standard. |

| i. | Albinos. |

| j. | If the colour of the hair is white (regardless if the nose/eyes are dark). |

| k. | Longcoated dogs (where the hair is soft, long, not tight — especially noticeable long inside and on the outside of the ears, long hair behind the front and rear legs, long hanging hair hanging from the tail). |

| l. | Longhair with absolutely no undercoat, where the hair from the back is parted in the middle and hangs down the side of the dog. |

Articles by Linda J. Shaw

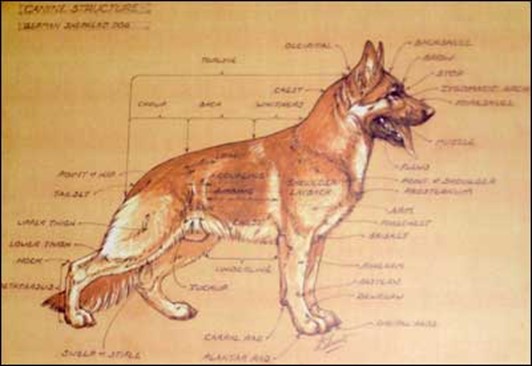

Conformation of the Working Dog

|

Written & Illustrated by Linda J. Shaw |

|

|

Correct angulation front and rear gives the breed its characteristic silhouette, as well as its athletic ability. However, while the breed typically shows a bit more angulation front and rear than most other working breeds, extremes should be avoided. That some is good does not imply that more is better. To simplify things, I’ve shown balanced dogs whose fronts match their rears. Balance is good of course, but I’d personally rather have a dog that was good on one end and less than perfect on the other, than one that was equally bad at both ends. The dog that lacks angulation will show a square profile, high in the rear, with little forechest. This dog can be quite effective at a gallop – this structure isn’t that different from that of the sight hounds – but his limitations will show up at the trot and in jumping. His lack of stride at both ends will result in a short stepping, choppy trot that uses a lot of energy. When he comes down off a high jump, he will be unable to rotate his shoulder far enough forward to effectively absorb the impact of landing. Dogs like this often try to jump outwards, coming down as much on all fours as they can, to keep the stress of impact off an inferior front. This sort of structure is of little consequence in a small dog such as a terrier, but in a larger, heavier dog it leaves the dog vulnerable to injury. |

We thank Linda for letting gsscc.ca publish these articles online.

Movement of the Working Dog

Written & Illustrated by Linda J. Shaw

We don't pay all this minute attention to the fine points of conformation just to have a beautiful dog, although that is certainly an inevitable bonus. The whole purpose of correct structure is to produce efficient movement, but that should mean movement at more than just the trot. A multi-talented breed must be proficient at every gait, as it will use them all in the various tasks expected of it.

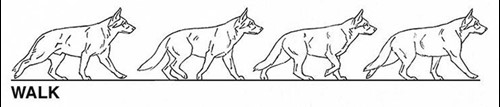

The GSD, or any dog, shows a characteristic mammalian walk (Fig 1 above). A typical sequence of steps would be the right rear, right front, left rear, left front, with no period of suspension. One can imagine that each stride of the rear, pushes ahead the foreleg on the same side as the animal proceeds ahead. This form of locomotion evolved from the reptilian gait, in which the right hind foot moves simultaneously with the left front foot, and vice versa. Mammals evolved longer legs, a more refined sense of balance and a stride which converged to the centerline of the body, all of which allowed a far wider range of gaits and much greater speed and agility. About all the typical reptile, such as crocodilians, can manage is to move their legs in the same sequence, but faster.

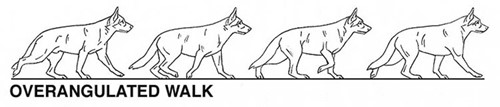

The GSD at the walk can show us quite a lot. While there is insufficient time in the average conformation ring to judge dogs at this gait, it actually has some advantages. Most obviously, the relative slowness of the gait makes it much easier to see. If a hock or pastern is bending or twisting slightly, it will be more apparent than at a faster gait when it might be missed altogether, despite the fact that any flaw which is observable at a slow gait will certainly not disappear under the pressure of greater speed. In overangulated dogs, hyperflexion of the joints, particularly the pastern and hock, will show up as the serious flaws that they are, rather than masquerading as part of an extreme, flying side gait (Fig 2 above). The tendency to single track can also clearly be seen. This is important, as it demonstrates the animal's sense of balance. Even a bull elephant walks with an elegantly precise, single tracking gait. Correct overreach will be apparent as well. A normal male shows an overreach of the hind foot beyond the footprint of the forefoot on the same side, of about eight inches. At a trot, it will be more. The overall outline of the dog's structure will be easier to see than when gaiting, particularly the topline, assuming it is not pulling into the lead (which is easier to prevent at a walk). If a dog shows a poor outline walking, it's not going to improve with speed.

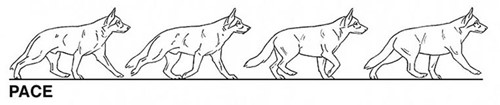

When the dog increases speed, he may briefly pass through a period of "shuffling". This is just a running walk, and is perfectly normal, although most animals built for speed don't do it very much or for very long. It's no different than the running walk or “tolt” of the Icelandic horse, in which it has been genetically selected and intensified. In wild animals, it is typical of really big animals, such as elephant and grizzly, whose mass makes suspension difficult or impossible. More typically, when increasing speed the dog may shift into a pace, with the legs on the same side moving in synchronization (Fig 3 above). This is not abnormal, nor is it an indication of structural problems. All dogs pace at one time or another. It's a gait that offers more speed than the walk without the energy consumption of the trot, which is probably why it is seen as a lazy gait. It appears clumsy because the body shifts from side to side, in exactly the same fashion as the camel, nature's best pacer. In fact, what is happening is quite interesting. Normally, a leg, front or rear, must be hauled forward by muscular work, and then thrust forward with more muscular work. But at the pace, the slight shift of the body to one side allows the legs of the opposite side to be swung forward by pendulum action, with very little muscular exertion. The camel uses this gait because of the incredibly harsh nature of its environment and the shortage of resources. It cannot afford to expend a drop more energy than is required. Generally, it is movement without any period of suspension. This would require extra speed and exertion, which the pace is not intended to provide. The Standardbred pacing horse specializes in a highly artificial, high speed, suspended pace because of breeding, training and special harnesses. For the horse, this gait prevents hoof interference and injury, allowing a huge overreach which is more difficult to achieve at the trot. These concerns don't apply to dogs, who use the pace as a more leisurely means of covering ground. For this reason it is not uncommonly seen in tired, aged, sick or unsound animals, and has been incorrectly construed as an undesirable gait which is necessarily the result of these problems.

We thank Linda for letting gsscc.ca publish these articles online.